Anne Lamott once said: “You are all the ages you’ve ever been.”

It’s true: My dad was all the ages he had ever been. It’s tempting to see and remember only the 70-year old guy who was overweight, his body wrecked by decades of smoking and alcoholism, high-cholesterol foods and too many orthopedic surgeries to count. The man who recently didn’t have enough energy to go up and down the stairs too many times but who still took my kids to the park, played legos with them in the floor, and found a way to always say yes to their requests. He was also the 35 year old father of two. He was the man with the suave blue convertible that he drove cross-country. The wild teenage boy who grew up on a farm and knew everything there was to know about hay and cattle and what made a good meal. He was the 20-something air force man who worked on Nightwatch and helped ‘catch’ the U2 spy plane as it landed on base. He worked all over the world—Germany, Greece, Mexico, Viet Nam—and always came home to us.

He’s the guy who, less than a year ago, shouted out “Daddy’s little angel!” at a professional event where I—his 35-year-old daughter-received an award in front of my peers. I know I’m lucky because I’m someone whose dad made sure I knew he was proud of me. I knew my dad loved me.

He’s the man who, despite having very little financial wealth, started saving money for my kids’ college from the day each of them were born.

He’s the man who took care of his parents—looked after them, their home, their affairs.

He was the rascal of a three-year-old who held the farm cat by the leg. The first-grader with the less-than-stellar report card.

His heart broke once when his dad died in 1998. He sat at his dad’s bedside and fed him, talked to him, held his hand. He’s the man whose heart broke again when his son, my brother, died in 2000. He sat with him at Lynchburg General Hospital in the Neuro ICU, willing him back to life after his body had worked so hard to try to heal what couldn’t be healed from the drunk driving accident. He’s the dad who held space for my grief too—even when his was more than he could bear. He’s the man who carried around enormous guilt and anger for what he felt was his part in Chad’s death. He’s the man whose heart broke a third time when his mom died in 2011. He saw her every single day. He brought chocolate to her—the woman who kept her beautiful figure until her death at age 98 and swore by her diet of farm food and daily desert, savored with joy.

My dad spent his years after retiring from the military in service to his community. He worked at a place that was once called the sheltered workshop—a place of employment for individuals with disabilities. He was so proud of them too and brought me by his office many times when I was just a kid to show me the good work they were doing. He worked a maintenance job for the County—cleaning buildings, shoveling snow. He worked at the County nursing home, supporting the work of the nurses behind the scenes, getting up in the middle of the night to give them rides to work when it was snowy or icy outside. He was what they called a swamper with Summit Helicopters—very physical labor outdoors in high temps and on the road for months. He was a truck driver for Loomis Fargo. He was a volunteer with the Rescue Squad. He was a security guard at Bedford Memorial Hospital. He sat with ECO patients while they waited for a bed. He helped ailing people get in and get comfortable in the ED, holding doors open and getting wheelchairs for those who were struggling to move. He brought refreshments to the nursing staff and was great at ‘shooting the breeze’ with the doctors when the nights were too long and hard. He loved taking care of people and protecting them.

He was a man who knew great heights–literally and figuratively; and a man who knew great depths. A man who experienced the joy of flight and the darkness of grief.

I think I knew that I was about to lose my dad. I had been in Florida for work the days before his surgery and I called him from the Tampa airport Sunday afternoon to wish him luck—and to say that I’d see him after he woke up. It’s no coincidence that my last really lucid conversation with him took place while I watched planes take off and land. We joked a bit—he sounded really good—and then he told me that he had eaten liver and onions for lunch at Forks Restaurant. I held my breath. Liver and onions was the last meal my granddaddy Woodrow ever ate. My dad fed it to him just days before he finally died. My dad knew the symbolism of that meal and I knew it. He never ate another real meal after that. Clear liquids only. Well, there were those powdered eggs…

In the hours and days following his surgery, he looked gray to me. His eyes were dreary and weak. His temperature wasn’t right. He felt like someone not getting better. I could feel myself detaching from him. He didn’t seem like my dad anymore. Each day I would leave the hospital and weep in my car before heading home—I had a sense that what was happening was much heavier than it looked. On Thursday from his room in the PCU, he began telling me about his biggest regrets—and checked in to see if I held any grudges against him. I promised him I did not. That I loved him. That I, too, had done things I wasn’t proud of. That I had let go of all that old pain. I skipped visiting on Friday—I went to my office in Roanoke, willing him to get better by me moving on with normal life.

Through all this, I was watching You Tube videos of the surgery he’d had; learning more about A-Fib; looking at diagrams of what his heart might have looked like. I asked Google questions about his chances of getting better. I wondered if he was ready to come home. I wondered if his body had really been ready for the surgery. I wondered why he wasn’t a candidate for the TAVR they were doing in Roanoke. He told me when he woke up on Monday that if he had known it would feel the way it did, he’d have rather died. He said he’d try–for those two grandkids.

When he came home, we visited. I took my kids to see him. We brought easter dinner and he didn’t touch it. We brought sugar free jelly beans and they were never eaten. The last time I saw him he looked like he had aged 20 years in a week. His speech was like someone else’s. His body was so tired. His breathing sounded like a man about to collapse. Short, labored, heavy. He couldn’t sleep. He didn’t have an appetite. I knew something was wrong. Everyone said it was normal. The home health nurse, the folks at the doctor’s office. This was all to be expected.

Tuesday, I called him on my way home from work. I told him that I had just put oil and coolant in my car, filled it up with gas, and replenished the wiper fluid. He liked it when my car was well-maintained. He said, “Mandi, I’m a mechanic. I always know what’s wrong and how to fix it. But something is wrong with me and I don’t know how it will be better. I don’t know what to do.”

The next day—Wednesday—the last day he lived, I called. Mom said he had had a better day—at least in the morning. He had gone outside and they got to sit on the porch together. The nurse was adjusting his meds to help with blood thickness. They felt like they were figuring out some new things to help him feel better. But by noon he was tired again and went to bed. I didn’t go that night. I felt in my gut I needed sunshine and rest. So I took a long walk alone and stayed home for the night. Then, at 3:30 in the morning, I got a call from my mom that he had collapsed. I raced to her home—just 5 minutes from mine—and we held each other as we believed we had lost my dad. The ambulance took him to BMH. We followed a few minutes later. When we arrived, we met Dr. Dove—whom he loved—in the doorway. He was gone.

I kissed him on his forehead. On the place that had hurt so badly when he was in the hospital.

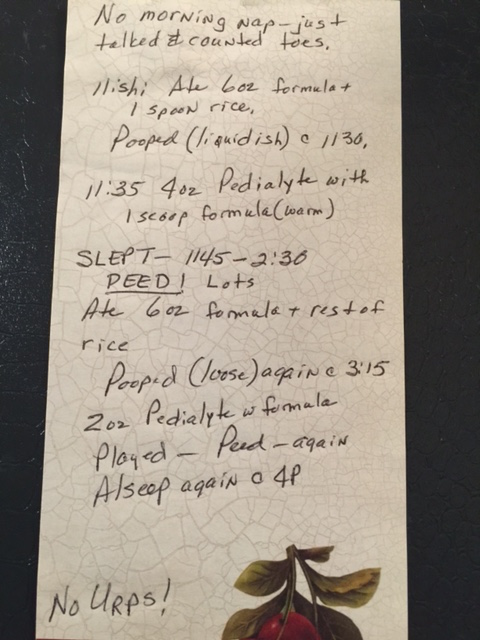

I stayed with my mom awhile and came back home at 6:30 Thursday morning. My oldest son, Owen, was awake. He asked me what happened and I told him Grandaddy Jimmy had died. He immediately threw up. I thought that was just about right. He was “#1 grandson” and my dad took care of him many, many days in his life. I still have notes from days my dad babysat him where he outlines, hour by hour, the activities of Owen. “Pooped, loose. Peed. Drank milk. Played with toes. Laughed. Pooped again. Spit up. Peed again. Went outside. Looked around.” This man who knew how the engine of the government spy plane looked was dedicating his days to the basic functions of my baby boy.

In the days following his death, my kids and I wrote him letters. They drew him pictures. We tucked those inside his pecan casket as we said our final goodbyes to the man who loved us so well. We dotted lavender oil on his forehead—the place where he felt so much pain. We said we were glad he has a new body now. And that we will see him again someday.

I tucked my youngest son, almost 5, into bed on Friday night. He asked where his heart was—where did it hurt when your heart hurt? So I placed his hand on his chest and he felt it. He said “I can feel it!” And then he said, “how can it be beating so hard when it is broken?”

My dad got my boys off the bus every afternoon. Life will not be the same for them when they arrive tomorrow and there’s no granddaddy Jimmy waiting.

Some of my hardest moments in this life have been with him. He was a man in pain—physical and emotional. His hurt turned inward as he drank himself numb and it turned outward as he hurt me, my brother, and my mom in ways we will probably never fully understand.

Some of my deepest lessons have been learned in my relationship with him. Forgiveness. Grace. Real love. You can only learn these lessons when you live in the open–vulnerable, human, real.

His death has broken my heart. And it has opened it. I have received enormous amounts of love, grace, support. My kids’ faith has grown 10 years in a matter of days.

My dad was an airplane mechanic, a janitor, a proud father, an alcoholic, a listener, a writer, a talker, a caretaker. He was a farm kid, an iconic older brother, a daredevil cousin, an affectionate gentleman. He was a playful grandfather and joke-teller. He was courageous. He was broken-hearted.

I’m grateful that the last three years of his life were sober ones. They were years that he was fully present for what was happening. Not numb anymore. I’m grateful he died at home—not attached to tubes and wires. I’m grateful that of all the dads in the world, he was mine. I’m grateful that my kids got to see him almost every day of their young lives. I’m grateful that he was never shy about telling me he loved me and was proud of me. I’m grateful that he was a living, breathing example of grace.

My dad was all the ages he had ever been. And now he is is ageless. Now he knows what it is like to have peace. To be healed. To have comfort. The kind of peace he never knew in this life.

What a tribute to your Dad. Took me a while to read this out loud to my husband as I got choked up and tears. Jimmy was one of a kind and yes he was all ages.

LikeLike

This is beautiful. Your dad is special. Recently he and I had some pretty interesting political banter on Facebook. I honestly think we both enjoyed it — although we agreed to disagree on a few things. Thank you for sharing your heart.

LikeLike